Americans love sports

Professional leagues have become multibillion dollar institutions as ravenous fans pack stadiums and arenas and spend even more time watching events on television at home. Americans also love shopping. According to the latest estimate, Americans spent $2.25 trillion at shopping centers last year. So it's only natural that entrepreneurial developers have found ways to marry two of country's most popular pastimes.

Take Arlington, Texas. There, a sports mecca is taking shape. To the south, construction is well under way on a new $1 billion, 80,000-seat stadium for the National Football League's (NFL) Dallas Cowboys — the largest professional football facility in the country. To the north sits the Ballpark — the 13-year-old home of Major League Baseball's (MLB) Texas Rangers.

But unlike in the past, the stadiums will not sit as idle islands in the middle of seas of parking, left dormant when it's not game day. Instead, the Columbus, Ohio-based developer Steiner + Associates and Hicks Holdings are knitting together a district between the two stadiums designed to host activities all year through the construction of Glorypark, a $600 million mixed-use project that will combine 1.2 million square feet of retail, 300,000 square feet of office, high-rise and mid-rise residential, and two hotels.

“We think sports teams help galvanize a community, but there are a whole host of things that need to be around a sports venue for it to succeed,” says Barry Rosenberg, president of Steiner + Associates. From his perspective, a town center like Glorypark is one of these things.

Arlington isn't the first city to try and create a successful sports and retail mix. The trend got its start in 1992 when the Baltimore Orioles moved from Memorial Stadium on Baltimore's outskirts to Oriole Park at Camden Yards smack dab in its then-moribund downtown. It was a bold move at the time — reversing the decades-long trend of professional teams leaving city-based stadiums for sprawling suburban facilities. It also set a new standard for ballpark design with its retro look incorporating exposed steel and brick and showcasing a view of Baltimore's downtown.

There, the Orioles enjoyed unprecedented success. In the team's first year at Camden Yards the Orioles set a then-franchise home attendance record of 3,567,819, a 1,000,000-fan jump from the previous season. At the same time, Baltimore's Inner Harbor was completely redeveloped and became host to a series of prosperous retail developments. In 1998, the NFL's Baltimore Ravens joined the Orioles downtown.

“Camden Yards was the first try at creating a place where sports fans could find entertainment outside of the ballpark,” says Ron Turner, vice president of RTKL & Associates Inc., a Los Angeles-based firm that designed Glorypark and L.A. Live, a $1 billion mixed-use project near Staples Center in downtown Los Angeles. The concept has matured so much that his firm has coined the phrase “extended play” to describe these types of entertainment/destination developments and districts.

What's happened today is that developers have learned from Baltimore — and other cities like Cleveland and Atlanta — and now are taking even bolder steps in the latest generation of stadium projects. Glorypark represents one of the most ambitious sports-centric retail developments proposed to date and is joined by others in progress like Meadowlands Xanadu in northern New Jersey, Atlantic Yards in Brooklyn, N.Y., Patriot Place in Foxboro, Mass. and Victory Park in Dallas. All are multibillion-dollar facilities whose developers seek to integrate sports and retail and create districts where the disparate ebbs and flows of those activities can coexist successfully.

But that doesn't make the process of getting these massive stadiums built easy — especially when teams come looking for public financing. Some cities — such as Seattle, Minneapolis and Pasadena, Calif. — have bristled when asked for money. Instead, teams are increasingly turning to private developers who can create a mix of development around stadiums, arenas, ballparks and even NASCAR racetracks to make the projects more palatable to politicians and citizens.

“There's an opportunity to create a greater place than just a stadium or ballpark where people come to see a game and then leave,” says Jim Baeck, vice president of Development Design Group Inc. (DDG), a Columbus, Ohio-based firm that has designed several mixed-use projects around sports venues.

If successful, Glorypark will complete the transformation of Arlington that began a decade ago. What used to be nothing more than a bedroom community sandwiched between Dallas and Fort Worth now will have its own identity. And none of that could have happened without the new Cowboys Stadium. The city of 367,000 was able to beat out its much larger neighbor, Dallas, and won the right to host the stadium by committing $325 million toward its construction — something Dallas officials refused to do. In part, it's hoping to reap the riches that can come to a city from hosting a Super Bowl, (something Arlington will do for the first time in 2011) an event that could create $200 million of new spending across the entire Dallas Metroplex and $30 million within Arlington alone, according to Craig Depken, a sports economist at the University of Texas at Arlington.

Generating buy-in

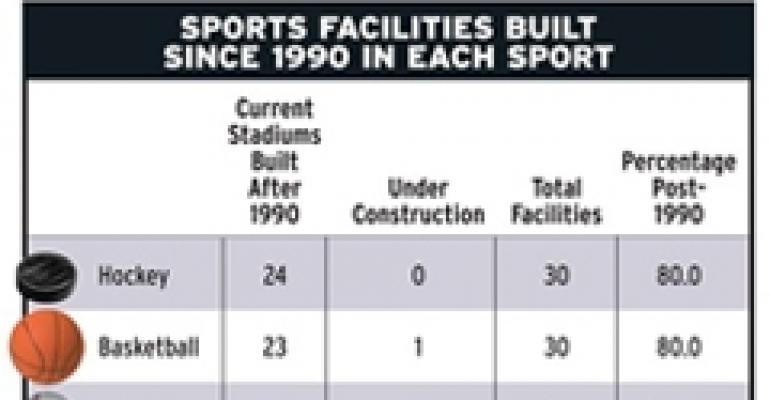

In the past two decades, it seems like almost every professional sports franchise (and minor league franchise, for that matter) has angled for a new stadium. For example, in baseball alone, 20 of the 30 teams play in stadiums built after 1990 and four more teams — the New York Yankees, New York Mets, Minnesota Twins and Washington Nationals — have stadiums under construction. That has been replicated in other major sports as well (see chart on p. 44). The lures, in part, are amenities at modern venues such as retractable domes, dozens of luxury suites for corporate sponsors and massive concessions areas.

But not every team is getting what they want. The vast majority of the stadiums got built with the aid of public financing. And now some cities are pushing back.

Consider the National Basketball Association's (NBA) Seattle Sonics. Team owner Clay Bennett is fighting with the city of Seattle over either replacing or renovating KeyArena, which was built in 1962 and completely rebuilt in 1995. He contends that a new arena would generate more revenue and has demanded a new $400 million arena be built. He set a deadline of October 31 for city leaders to decide whether they're willing to finance a new facility; if not, he says he will relocate the team.

“The willingness to subsidize sports projects has decreased dramatically,” notes Roger Noll, a professor of economics at Stanford University and author of Sports, Jobs, and Taxes: The Economic Impact of Sports Teams and Stadia. “Studies have proven that new sports facilities don't solve economic problems, they just make them worse.”

A study that examined 37 metropolitan areas with at least one athletic franchise from 1969 to 1996 found that stadium projects have a negative impact on per capita income levels. Constructing an arena to accommodate an NBA franchise reduces real per capita income by almost $73 in each of the 10 years following the construction of the arena, according to the study, which was conducted by Dennis Coates and Brad Humphreys and published in Regional Science and Urban Economics. A similar effect was found regarding MLB franchises as well.

What works better is when facilities are joined with a variety of uses that can keep areas active. By pitching facilities as a component of a larger project, owners are hoping to change the minds of public officials and citizens that might oppose projects.

“It's simple economics to realize that these multiuse developments are far better for their cities than a [stand-alone] stadium or arena,” Noll adds. “Sports venues alone are just big black holes that have the ability to depress the neighborhoods in which they're in. So, if you're going to have a stadium, it's better to embed it in a larger development.”

But, there are also opponents who are not just critical of sports venues, but also the mixed-use projects around them, particularly when it comes to retail and restaurants. “Much of what is sold at retail stores near stadiums would have been sold at other existing retail outlets so estimates of gross sales greatly exaggerate any net effect,” points out John Siegfried, an economics professor at Vanderbilt University in Nashville.

From Siegfried's perspective, there's only one way sports-centric retail can really provide positive economic benefits — the retail has to be completely and totally unique.

Lessons learned

Bringing in new retail is exactly what Boston-based Kraft Group is trying to do with Patriot Place, a one-million-square-foot mixed-use district adjacent to five-year-old Gillette Stadium in Foxboro, Mass.

Small shop retailers and restaurants will occupy 80 percent of the retail space at Patriot Place, according to Peter Belsito, founder of Strategic Retail Advisors, a Boston-based firm handling retail leasing at Patriot Place.

And while not all of the retailers are unique to the market, there are some notable new additions, including the region's first Bass Pro Shops.

The trend in sports-facility construction today reverses the pattern of a generation ago. Taking advantage of innovations in steel and concrete construction in the 1960s and 1970s, teams abandoned cramped and dated downtown parks for new multipurpose facilities in the suburbs. Parks in Philadelphia, St. Louis, Pittsburgh, Seattle, Houston and Cincinnati — among others — shared similar design aesthetics as donut-shaped, symmetrical stadiums that could host both football and baseball games.

The problem? Most of these facilities were built on greenfield sites in seas of asphalt parking. They became islands that buzzed with life on game days, but sat dark for half to three-quarters of the year.

“We're really experiencing a sea change where people are realizing that they're not taking advantage of a venue that attracts a lot of people and they're not using the land in a smart way,” Baeck says.

Pittsburgh learned from its mistakes, says Frank Kass, CEO of Continental Real Estate Cos., the Columbus, Ohio-based firm that is developing the land around the NFL's Pittsburgh Steelers' six-year-old Heinz Field and the MLB's Pittsburgh Pirates' PNC Park, which opened in 2001. Continental's project, North Shore, includes a mix of office and retail space downtown, right at the point where the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers come together to form the Ohio River.

Previously, the Steelers and Pirates shared Three Rivers Stadium, a multipurpose stadium that was surrounded by acres of blacktop parking. The city thought Three Rivers Stadium would spur development; instead, it ended up being a big black hole for more than 260 days a year.

“The problem with those round buildings with acres of parking was that they didn't connect to the community,” Kass says.

So Pittsburgh started from scratch. It imploded Three Rivers Stadium in 2001, replacing it with Heinz Field and PNC Park and giving the Steelers and the Pirates joint development rights to the land. The teams chose Continental to redevelop the site.

A master plan was created for the 24 acres surrounding the stadium and ballpark. Today, the site boasts 500,000 square feet of office space and ground floor retail in three office towers. Construction on a new nightclub and a Hyatt-flagged hotel will begin in 2008, along with another office building.

Must have master plan

While the Pittsburgh project isn't as large as some of the others, it illustrates the growing role master-planning is playing.

“We've seen an evolution with these sports-related developments — the scale continues to grow — they're larger and more complex,” says Jon Cordish, vice president of the Cordish Co., a Baltimore-based company that has several sports “districts” under development or in the planning stages, including Ballpark Village near Busch Stadium, home to the MLB's St. Louis Cardinals. “We're now developing cities within cities — multicity block projects that encompass every commercial use.”

Cordish's track record includes projects near Baltimore's Camden Yards where it built the Power Plant and Power Plant Live! The company's Ballpark Village will be even more ambitious than its Baltimore work, covering six city blocks and connecting directly to Busch Stadium. Cordish is developing the $650 million mixed-use district with the Cardinals. It will feature approximately 450,000 square feet of retail/entertainment, 1,200 residential units, 300,000 square feet of office and 2,000 parking spaces.

“The most important thing for these kinds of projects is parking and circulation of both cars and people,” says RTKL's Turner. He contends that the high-profile $1 billion-plus Meadowlands Xanadu project in Secaucus, N.J., outside Manhattan, suffers from the lack of a master plan.

The 2.2-million-square-foot project, a joint venture between Colony Capital, Dune Real Estate Funds and KanAm USA Management XXII LP is located next to Meadowlands Stadium, which will house the New York Giants and New York Jets NFL teams beginning in 2010.

With so many different organizations involved, it's no wonder that they all have conflicting interests and are fighting over traffic and parking. Colony Capital declined to talk about the project, and the New Jersey Sports and Exposition Authority was not available for comment.

In Washington D.C., on the other hand, the city created a master plan for the Ballpark District — a 60-acre swath of land surrounding a new 41,000-seat ballpark where the Washington Nationals MLB team will play starting next year. The Ballpark District, located one mile south of the U.S. Capitol, will include 465,000 to 785,000 square feet of retail and restaurant uses; 350,000 to 1.6 million square feet of office space; and 1,600 to 3,000 units of housing.

One of the projects under construction in the Ballpark District is Half Street. Developed by San Francisco-based MacFarlane Partners and Washington, D.C.-based Monument Realty, Half Street will include residential, office and retail space, along with a hotel and public parking garage. Phase I, which began construction in January 2007, consists of four adjacent buildings offering more than 250,000 square feet of office space plus 50,000 square feet of retail space, about 300 residential units, and a 200-room boutique hotel. It will open by the end of 2009.

Forest City also has a project under development in the Ballpark District, The Yards, a mixed-use project built on the site of the Washington Navy Yard. When completed, the project could have as much as 1.8 million square feet of new office space, 2,800 residential units (both for lease and for sale) and up to 400,000 square feet of retail.

However, Forest City started working on The Yards well before Washington announced the new ballpark, according to Deborah Ratner Salzberg, president of Forest City Washington Inc. “We believed in this project because of the surrounding demographics and the river,” she says. “This project stands on its own, with or without the ballpark. But, we do believe the neighborhood will develop much faster with the ballpark.”

There's no one-size-fits-all approach to sports facilities today. While there has been a push to bring more stadiums into downtowns, some are still built in suburban settings. But city officials have spurred the push inward by doing what they can to lure the action back inside city limits.

“Cities are trying to be more creative and aggressive in attracting development around the sports venues because of the multiplier effect — all of the surrounding development will help strengthen the economy and add to the tax base,” says Lew Feldman, a partner with Goodwin Proctor LLP who structured the bond finance package offered by the city of Los Angeles for the development of L.A. Live, a four-million-square-foot, $1 billion sports, residential and entertainment district adjacent to Staples Center and the Los Angeles Convention Center.

L.A. Live, which is being developed by Los Angeles-based Anschutz Entertainment Group (AEG), will feature a 7,100-seat, live-performance theater; a 54-story, 1,001-room convention hotel; a 2,200-capacity, live-music venue; a 14-screen Regal Cineplex; and entertainment, restaurant and office space. Designed by RTKL, L.A. Live is scheduled to open in early 2008.

New anchors

The strongest proponents of sports-centric retail construction believe arenas and ballparks can “anchor” neighborhoods, creating an identity for the area and encouraging development.

In Phoenix, for example, RED Development recently broke ground on CityScape, a 2.5-million-square-foot, mixed-use project that encompasses three city blocks. The project sits across the street from US Airways Center, where the Phoenix Suns NBA team plays, and about two blocks from Chase Field, where the Arizona Diamondbacks MLB team plays.

RED Development partnered with Naples, Fla.-based Barron Colliers Company to develop CityScape out of largely vacant lots. Currently, the seven-acre site hosts just an old department store, several parking lots and a city park.

About five million people attend Suns and Diamondback games annually, but leave immediately afterward because there's nothing else to do in downtown.

Dallas is another city that had trouble creating a lively downtown. The development of American Airlines Center (AAC) is often credited with revitalizing the urban core. Situated on 75 acres on a former brownfield site, the $420 million multipurpose arena opened in 2001 as the new home of the Dallas Mavericks NBA team and the Dallas Stars NHL team.

AAC is part of a master plan by Ross Perot Jr. called Victory Park, which includes 12 million square feet of office and retail space along with hotels, condos and apartments. The state's first W Hotel & Residences is already open, and by the end of 2008, 620,000 square feet of office space will be complete, along with roughly 50 retail stores and restaurants.

“It's an advantage to have AAC as part of Victory Park,” says Bill Brokaw, vice president of Hillwood, which is Perot's development company. “With well over 200 events per year, the arena creates a significant amount of energy that will really feed into the surrounding development.”