One indicator that Florida still trails the recovery in the national retail real estate market is the fact that investors there continue to show preference for class-A grocery-anchored shopping centers, while across the country they’ve moved on to riskier product types.

With the Sunshine State still carrying too much housing stock and its unemployment rate above the national average, investors have avoided risk and gravitated toward necessity-based retail in markets with established populations.

The good news is that despite the lingering macroeconomic concerns, investment sales volume in Florida is rising. Year-to-date in 2011, $2.1 billion in retail property has changed hands—a 33 percent increase over the same period in 2010, according to Real Capital Analytics (RCA), a New York City-based research firm. Investor demand ranges from institutional capital to publicly-traded REITs like Federal Realty Investment Trust and Weingarten Realty to private equity buyers like Blackstone to foreign buyers from Germany, Canada and Israel.

But the increase in interest is primarily a reflection of nationwide trends, including low interest rates and greater certainty about true property values, says Dennis Carson, senior vice president with the Florida team of the retail sales group at CB Richard Ellis. The state itself continues to face major issues, including its still unresolved housing glut and high unemployment statistics.

In June, sales of existing single-family homes fell 4 percent compared to the same period a year ago, to 17,597, according to Florida Realtors, the local branch of the National Association of Realtors. The median price of a single-family home fell 2 percent year-over-year, to $138,000. The larger part of the extra inventory lies in the suburbs, with rising fuel prices playing a role in people’s unwillingness to buy too far outside city limits, according to Bobby Eggleston, vice president of real estate with RMC Property Group, a Tampa-based full-service real estate firm.

That’s why the vast majority of investors looking for acquisitions in Florida want core assets in primary markets, according to Carson—preferably grocery-anchored centers or power centers. Demand wanes when it comes to lesser quality properties in smaller markets, or product types that are more reliant on discretionary spending. Private REITs tend to be among the few buyers willing to buy assets in secondary and tertiary markets because they are looking for greater yields than institutional capital, Carson says.

Cap rate compression

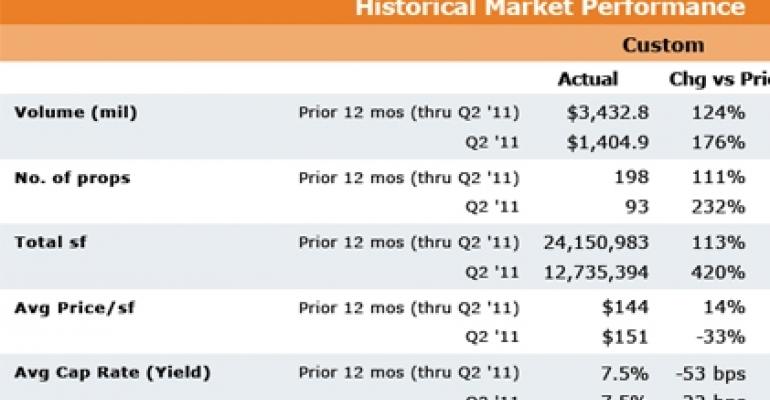

Interest in class-A centers is strong enough that cap rates have almost returned to peak market levels. RCA estimates that over the past 12 months cap rates for retail assets in Florida have dropped 53 basis points, to 7.5 percent. The average price has gone up 14 percent, to $144 per square foot.

“There has been an increase in both the sales volume and the price of properties, particularly within the neighborhood category,” says Mike Milano, managing director of retail services in the Tampa office of Colliers International. “For a Publix-anchored shopping center, those are trading for a premium price that’s almost reminiscent of the peak of the market in 2005 and 2006.”

Class-A multi-tenant centers in markets like Miami Beach and Kendall, for example, trade at cap rates in the low to mid-7 percent range, according to a mid-year report from Marcus & Millichap Real Estate Investment Services. If in addition to a prime location and a credit-worthy anchor the property offers upside either through below-market rents or future redevelopment opportunities, cap rates can drop into the low 6-percent range, says Carson.

Class-B and lower centers that still boast a good location trade in the 8.5 percent to 9 percent range, according to Marcus & Millichap.

“There is still a very steep pricing curve the further down the quality spectrum and the further from the primary markets you go,” Carson notes.

Slow resolution

Opportunistic investors have seen a limited number of distressed assets hitting the market in Florida, according to Milano. There is plenty of cash waiting for those kinds of properties, especially since many of the distressed centers in the state were new construction projects that fell into default because of over-leverage rather than property issues.

For the moment, however, the banks in Florida have been disposing of distress through loan sales rather than direct property sales, notes Carson.

“Companies and institutions are all trying to seize real estate because it’s one of the primary wealth builders and they are trying to buy low and sell high,” says Milano. “But we’ve still not seen that number come through.”