Some of the nation’s largest commercial real estate investors — pension funds — are seeing signs of financial recovery, but they are under increasing pressure to cut the rate of return they expect to receive on their investments.

Pension funds invest in a variety of asset classes, including stocks, bonds, private equity funds and real estate. On average the nation’s public pension funds earmark about 10% of their total portfolios to real estate.

In early September, the New York State Common Retirement Fund, the country’s third-largest public pension fund with $124.8 billion in total assets under management, dropped its overall annual rate of return assumption from 8% to 7.5%. The adjustment followed a 25.9% loss for the fund in the fiscal year that ended March 31, 2010.

In an ominous warning, New York State Comptroller Thomas DiNapoli said he expects more plans to follow suit in the near future. According to the National Association of State Retirement Administrators (NASRA), since 1985 public pension funds have exceeded their assumed rates of return on investments. On its face, there seems little reason for a change.

8% return still the goal

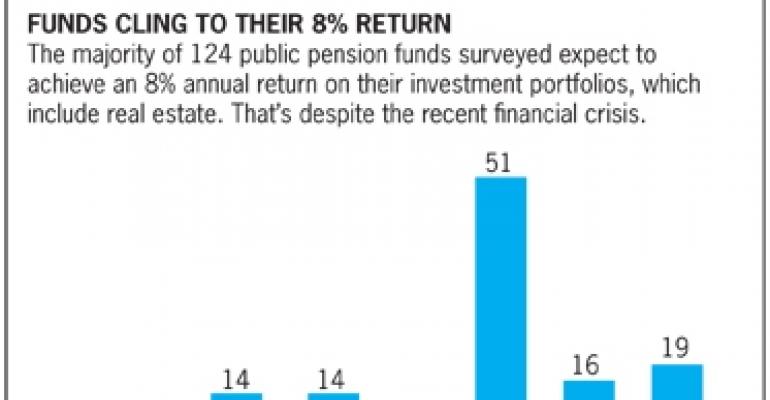

In a recent NASRA study, 51 out of 124 public pension funds are assuming an annual return of 8%, and 35 assume a return of more than 8%. The lowest assumption was one plan targeting a 7% return (see chart).

“Those return goals are based on years of actuarial data and are used to measure unfunded benefit liabilities,” explains Robert Bach, senior vice president and chief economist at Grubb & Ellis. “It’s my understanding that they are reviewing their return expectations across the board as a result of recent underperformance and also very low inflation.

“I think there’s a push toward more conservative expectations in the future — less chance of unfunded liabilities when the clock strikes 12 and benefits are due to be paid,” adds Bach.

As it turns out, the notion of adjusting rates of return is a fairly recent development. Until the 1980s, most public pension funds invested in bonds and low-yield investments. But thanks to sky-high interest rates in the late-1970s and the funds’ drive for diversification — including real estate investments — they were prompted to raise their return assumptions.

Return assumptions are important because they are the foundation for paying out liabilities to fund participants. Of all the assumptions used to estimate the cost of a public pension plan, none has a larger impact on the plan’s costs than the investment return assumptions. Over time, earnings from investments account for about 60% of the revenues for most public pension plans.

Lowering assumptions is fraught with pitfalls, since it would require funds to set aside more money to fund past and present liabilities. For example, the New York State Common Retirement Fund’s lower assumption will mean a $900 million increase in funding from state and local governments in New York starting in February 2012.

This comes at a time when most state and local governments have become strapped for cash and cut public services thanks to the recent financial crisis, and they have little to no extra money to help fund liability shortfalls.

Mixed performances

Certainly some pension funds are performing better than others, and at the moment many funds appear to be on the road to recovery. The California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS), with $207.3 billion in total assets under management, recently reported a 10.3% return for the fiscal year that ended July 31, 2010. But the fund’s return year-to-date through July is only 4.24%.

CalPERS currently has $15 billion in real estate assets, and is targeting a total allocation of nearly $21 billion. But the asset class has proved to be a laggard when it comes to performance. From Aug. 1, 2009 to July 31, 2010, CalPERS’ real estate portfolio recorded a loss of 35.8% versus a planned return of 6%.

The story is similar for its in-state neighbor. The California State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS) posted a 12.2% return for its fiscal year that ended June 30, 2010. The double-digit return beat its target rate of 8%, but losses of 25% in 2008 and 3% in 2009 damped the fund’s three-year rolling average.

Real estate, which accounts for $13.3 billion, or 10.1% of the CalSTRS’ total asset base of $132 billion, was the only laggard among asset classes, with a 12.4% decline for the latest fiscal year. Stocks were the top performer, returning 14.5%.

The Kansas Public Employees Retirement System returned 14.9% for its fiscal year that ended June 30. Real estate was a key contributor, returning 12.1% versus a benchmark 7.4%.

But real estate was the only asset class to show negative returns for the Pennsylvania Public School Employees’ Retirement System, dropping 10.3% for the year that ended June 30. The system saw a total return of 14.59%.

Historic data from the National Council of Real Estate Investment Fiduciaries (NCREIF) bears out the cyclical fluctuations inherent in commercial real estate returns. The NCREIF Property Index Return, which measures the performance of institutional-quality commercial properties, tallied an 18.7% return at the peak of the property markets in 2005, but the index fell by 17.9% in 2009.

Many commercial real estate industry insiders are unsure about exactly where the pension funds should peg returns for the future. Ted Leary, president of advisory firm Crosswater Realty Advisors based in Los Angeles, puts it bluntly. “That’s the $64-plus billion question. Only time will tell.”