“The bottom line is that the world is a mess. … I worry about how all of these events play together and the challenges it will have for all of us in the commercial real estate business, the service sector and the global economy.”

— John C. Cushman III, co-chairman of the board, Cushman & Wakefield Inc. speaking at the Urban Land Institute’s Fall Meeting in Los Angeles in October.

The commercial real estate industry always has an eye on Washington, D.C. The industry’s trade associations keep tabs on legislation, organize lobbying and its political action committees funnel contributions to candidates.

From time to time, a law comes up that the associations rally around—for example, the periodic calls for changing how carried interest is taxed. But, for the most part, what happens in the nation’s capital is background noise. The industry’s pros spend their time focusing on deal-making, not worrying about how politics may affect that.

Except for the 1930s and 1960s, mass protests and work stoppages have not typically been major features of the American political landscape. That’s in contrast to Europe and the Global South, where such events are more common. Indeed, one factor that has attracted capital and business to the United States has been its stable political environment. And that’s the way commercial real estate investors like it.

Today, however, political unrest is asserting itself in America in ways unseen in decades, creating the most uncertain political climate many commercial real estate investors have witnessed.

No one has any idea how the impasse in Washington will resolve itself.

“I have been around a long time and I haven’t seen anything like this,” says Stan Ross, chairman of the board of Southern California Lusk Center for Real Estate. “In the old days of the Ways and Means Committee, they would come in, talk, debate and beat each other up. But they would come up with solutions. … Today we just seem to have a standstill on both sides.”

Mass movements make the outlook even dicier. That normally wouldn’t be a problem. But at the heart of the anger is the economy and the financial sector. Financial regulation and tax reform are on the agenda. How things play out will affect commercial real estate.

To be sure, the uncertainty has not stopped deal activity. Properties are being traded and leases are getting signed, albeit at a slower pace than the industry would probably like.

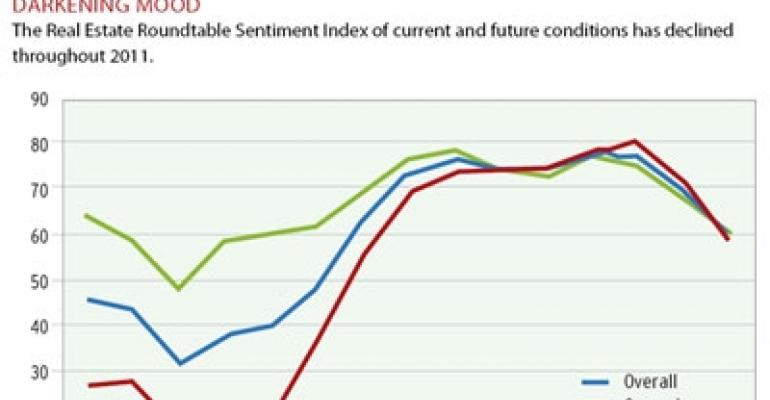

But concerns about Washington’s inability to address fiscal and tax policy challenges, as well as new regulatory requirements, were factors cited for declining confidence in the commercial real estate recovery in a recent survey by the Real Estate Roundtable, a non-profit public policy organization based in Washington, D.C. Other issues cited included the state of the economy and lagging industry fundamentals.

The Sentiment Index dropped to 59 (on a scale of 100) in the fourth quarter. It is down from 77 in the second quarter and at its lowest point since 2009.

Ultimately, who wins the 2012 election, how emergent mass movements shape pending legislation, how the Dodd-Frank and health care reform acts are enacted, how federal deficit reduction affects government office space, how the tax code changes and how government policy affects the economic recovery will be key questions over the coming months and years.

“I don’t care what political candidate or party you favor, I think our only hope is coming out of the election a year from now, that we have an executive branch and a Congress that is more inclined to work together to solve these problems,” says Jim Connor, a senior executive vice president at Duke Realty Corp. in Indianapolis. “Clearly what we have today isn’t doing that, which is why we have political gridlock.”

The political scene

The gap between the two major parties (and control of the two houses of Congress being split) has made it virtually impossible to pass legislation.

The dysfunction reached its apex this summer when Congress nearly did not raise the nation’s debt ceiling—something that has happened 102 times since 1917 without controversy. The delay brought the U.S. to the brink of default and the political impasse led Standard & Poor’s to lower the nation’s credit rating a notch soon after the drama passed.

Things are so bad that a recent CBS/New York Times poll found Congress’ approval rating at an unfathomably low 9 percent—a number that matches the current national unemployment rate.

Part of what’s fueling the unrest is the weak pace of the recovery from the 2008 recession. The level of job creation in recent months has just barely exceeded the pace needed to keep up with population growth. And it is well short of the rate necessary to make up for the millions of jobs lost in the last recession.

The employment situation is also worse than the official numbers suggest. The labor force participation rate was at 64.2 percent at the end of October. That’s up from a cyclical low of 63.9 percent reached in July—but well short of the peak of 67.3 percent reached in early 2000. When counting underemployed, the adjusted unemployment rate is north of 16 percent.

The problem is not that firms don’t have money or are not profitable. In a July report, Moody’s estimated the 1,647 U.S.-based companies it rates had $1.2 trillion in cash, including short-term investments, at the end of 2010, up 11 percent from the end of 2009. Meanwhile, economists from Northeastern University in report this summer found that since the recovery began in June 2009, “corporate profits captured 88 percent of the growth in real national income.” Yet repeatedly, corporate executives have cited the broad level of uncertainty as to why they are not investing or hiring.

Meanwhile, the U.S. government remains divided on key issues across the board—from the contentious vote to raise the debt ceiling to current debates on how to reduce the $14.94 trillion federal debt and cut deficits projected to be more than $1 trillion annually.

In addition, the sovereign debt crisis in Europe, the slow pace of GDP growth in the United States and the specter of a double-dip recession have only contributed to the dissatisfaction. The Conference Board projects U.S. GDP growth to come in at 1.5 percent in 2011 and slow to 1.1 percent in 2012.

All of this has contributed to a worsening political scene. The 2012 election cycle is underway. No frontrunner has emerged on the Republican ledger and the overall outlook remains cloudy.

More significantly, dissatisfaction with the two main political parties has led to a rise in populism the likes of which the U.S. has not seen in generations. The Tea Party movement came on the scene in early 2009, helped shape the outcome of the 2010 midterm elections and has a continued influence in Congress, through the Tea Party caucus.

On the Left, the “Occupy” movement has emerged. What began with a few hundred Occupy Wall Street protesters in Manhattan in September has spread. Encampments are now in dozens of cities, although many, including Zuccotti Park in Manhattan, have been cleared out by police in recent days. Their actions are becoming bolder. In Oakland, thousands turned out for a “general strike” that closed the Port of Oakland, the fifth largest U.S. port, for a day in early November.

To date, the Occupy movement has kept an arm’s length from electoral politics. But it has affected rhetoric, most crucially, from the commercial real estate industry’s perspective, in there being increasing talk of corporate greed and income inequality and a potential push for higher marginal tax rates.

Both movements, far from being fringe phenomena, enjoy some measure of popular support. A recent Quinnipiac University national poll found that 31 percent of respondents had a favorable opinion of the Tea Party Movement, while 30 percent also had a favorable opinion of the Occupy movement.

What both sides have in common is anger at the status quo. But the two see different culprits as the cause. For the Tea Party, it is the government that is the problem. For Occupy Wall Street, it is the financial sector and large corporations more generally.

Jeffrey DeBoer, president of the Real Estate Roundtable, says that these movements are exacerbating the rift between Democrats and Republicans.

“It’s forcing both parties to go to their extremes,” he says. “And it’s making it much more difficult to find a compromise and a negotiated way forward in the middle. That contributes to the policy gridlock that has grabbed a hold of Washington and that will probably have a hold on Washington until after the 2012 elections.”

In the long-term, what might be most troubling for the industry is the fact that the Occupy movement is full of members of the massive Generation Y demographic. Students and recent graduates saddled with large amounts of student debt and facing dim job prospects are lashing out and expressing distrust with major financial institutions.

For years the commercial real estate industry has pointed to the 80-million member Generation Y as the basis for long-term growth. But a section of these supposed future employees, consumers, investors and tenants are instead living in tents and occupying public space.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, there are now 3.3 million unemployed workers between the ages of 25 and 34—double the level from four years ago. Moreover, there are 2 million unemployed graduate students—triple the number from 2007. And they are saddled with a mountain of debt. According to recent estimates by The Economist, the amount of outstanding student loans will soon reach $1 trillion.

How does this tension break? Many in the industry are focusing on the 2012 election as the catalyst that will clarify many of the other political questions.

“The election is an inflection point,” says Bill Krouch, CEO of markets at Jones Lang LaSalle in Chicago.

For its part, the commercial real estate industry seems to be leaning Republican, according to NREI analysis of Center for Responsive Politics data on campaign contributions. Through the end of October, 10 political action committees connected to major commercial real estate associations had donated $1.3 million to federal candidates, with 63 percent of the contributions going to Republicans. That’s the highest percentage going to Republicans since the 2006 cycle. But there’s still a lot of time for money to be doled out. The level of contributions is about one-third the total that the PACs contributed in the 2008 and 2010 election cycles.

Jobs, jobs, jobs

Although the apartment industry has benefited from the rise in foreclosures and decline in homeownership, the political quagmire is contributing to what has been a slow recovery across other sectors of commercial real estate.

After peaking in early 2010, industry statistics show that industrial and office vacancies are still hovering near 10 percent and 17 percent respectively. Mall vacancies inched slightly higher to 9.4 percent in third quarter, while vacancies at neighborhood and community centers remained flat at 11.0 percent, according to data from Reis Inc.

Recovery in the office market in particular remains heavily dependent on job growth, which although trending positive, is hardly booming.

“Until you can get corporate and institutional America hiring, get some growth in the economy, companies are not going to need a preponderance of new office space,” says Duke Realty’s Connor.

The lack of cohesive leadership and decision-making is creating a drag on job growth and consumer confidence, and producing widespread frustrations across the commercial real estate industry.

“We would love to be in a position to develop new properties, but given the state of the overall economy and what the vast majority of local markets look like, you can’t justify new development. The need just isn’t there,” says Connor. Duke continues to move forward with select build-to-suit and medical office projects, but its development pipeline is a fraction of what it was five years ago.

In addition, the uncertainty in political leadership is widespread around the globe, from the European sovereign debt crisis to upheaval in the Middle East. “You are seeing a similar lack of decisive actions being taken at leadership levels in Europe and the United States,” says Richard Kadzis, vice president of strategic communications at Atlanta-based CoreNet Global, an association for corporate real estate professionals.

Companies are growing and making profits. However, the mandate for cost-cutting and doing more with fewer people remains. “Until the governments of the Western world figure out how to correct the debt and finance crisis that they are facing, we are going to have a harder time as business people rationalizing more hiring or higher levels of spending,” says Kadzis.

Tackling the deficit

The federal deficit has been at the center of political discourse for much of the past year, and the proposed solutions have focused on reducing expenditures. Many Republican members of Congress, in fact, have pledged to vote against any bills that introduce new taxes.

But the danger to the industry from the rise of the Occupy movement, and whether Congress responds, is that there could be more pressure on the revenue side of the equation.

Carried interest is a perpetual boogeyman. Carried interest is a share of profits in partnerships paid to the manager of a partnership.

Currently, carried interest is taxed at 15 percent, the capital gains rate. Because hedge funds and private equity investors use the carried interest rule to pay lower taxes, there has been call for reform. Many would like to see that raised to match the highest marginal income tax rate, currently 35 percent.

However, what’s often lost in the debate is that more than 40 percent of all investment partnerships are for real estate and would be affected by the legislation.

In late October, nearly 20 industry trade groups sent a joint letter to the Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction regarding carried interest. Part of the letter explained that carried interest “is the way to reward the general partner in a real estate business venture for taking on the countless risks and liabilities associated with long term real estate projects, such as potential environmental concerns, operational shortfalls, construction delays and loan guarantees. No matter how it is spun politically, raising taxes on carried interest is bad for the entrepreneurs and small businesses that need capital to innovate, grow, build and create jobs.”

“We thought it would go away, but it keeps coming back,” Ross says.

Carried interest is not the only tax reform that could affect the sector.

“Some members of Congress are looking at leverage and saying, ‘Let’s look at the tax code and see which tax sections fuel high leverage.’ What they are saying is that perhaps the tax code should be reformed to discourage high leverage,” Ross says. “Well, the highest leverage investors are in real estate.”

For his part, DeBoer thinks that while proposals will be bandied about in the next year, there are unlikely to be any real proposals put on the table and voted on until 2013. Still, he thinks it is important for the industry to be active and vocal in shaping the discussion.

“Now is the time to double down on relationship-building,” DeBoer says. “Even if solutions cannot be enacted now, having a dialogue is critically important and helps you be prepared when the logjam does break. And it will break at some point.”

Finding a silver lining

To be sure, uncertainty in Washington has not brought deal-making to a halt. In fact, investment has benefited from some of the turmoil that has roiled financial markets.

“The political uncertainty here and abroad has contributed to wild gyrations in financial markets,” says Brian Stoffers, president of CBRE Capital Markets in New York. Hundred point swings in the Dow Jones Industrial have become the norm in recent weeks. There also has been a compression in the U.S. 10-year Treasury yield, which dropped as low as 1.72 percent in September.

Given that backdrop, both foreign and domestic investors are turning to core commercial real estate as a safe haven. Despite all of the turmoil in Washington, the U.S. political environment is still considered to be relatively stable compared to what is happening in other countries, notes Stoffers. Core real estate properties are attractive because they are hard assets, and there is the potential for income growth. “So there has been a big resurgence in demand for core real estate assets this year,” he says.

The $130.3 billion in commercial real estate sales that have occurred during the first three quarters of 2011 already exceed the $126.0 billion in properties that changed hands in 2010 and the $55.1 billion in properties that sold in 2009, according to New York-based Real Capital Analytics.

The flip side is that investors that had been warming up to properties in secondary and tertiary markets have since pulled back.

“Before the last downdraft in September and October, we did see investors migrating into secondary and even the best of the tertiary cities,” says Stoffers. But as the uncertainty over the European debt crisis flared up, buyers froze in their tracks, he adds.

Although the frustration with the dysfunction in Washington is widespread, some industry observers are optimistic that real business growth is returning. Companies are not on the sidelines wringing their hands. The mandate in the corporate arena is to push forward with growth. Companies have the cash reserves, and they are working to find the right markets, the right talent, the right supply chain, or the right cost levels to expand and keep that momentum going, adds Kadzis. In addition, companies recognize that it is a tenant’s market, and they are taking advantage of that. “Decisions today may be somewhat more challenged, and include a far more complex set of dynamics, but I don’t think that decisions are being put on hold,” he adds.