Amid rising unemployment and weakening demand for space, the U.S. office vacancy rate rose to 13% in the third quarter. But it could climb as high as 19% if companies consolidate their space to reflect smaller workforce levels.

Analysts fear that the nation’s job losses are not yet fully reflected in the office vacancy rates. If employers across the country cut their space needs to match layoffs when tenants’ leases come up for renewal, soaring vacancies could later wallop the office sector.

The nation’s unemployment rate reached a 26-year high of 10.2% in October, and more layoffs are expected in months ahead. Meanwhile, the gap between the current vacancy rate and the rate statisticians project based on the unemployment rate stands at six percentage points, according to Bethesda, Md.-based research firm CoStar Group.

“We call it phantom vacancy. Phantom vacancy can mute any recovery that we do see down the road,” says Jay Spivey, senior director of analytics at CoStar.

Currently, without a sharp adjustment in leasing requirements to get rid of the unused space, the firm expects the national vacancy rate to peak in the third quarter of 2010 at about 16%.

It could take two more years, until the third quarter of 2012, before landlords begin to see positive gains in rent. That is because all the excess supply in the market needs to be absorbed before vacancies tighten sufficiently to warrant higher rents.

The current employment picture does not bode well for the office market. The volume of negative net absorption has not reached the level expected for such a high number of job losses.

In the first quarter of 2009, the office sector recorded negative net absorption of close to 20 million sq. ft. nationally, compared with an expected negative net absorption of nearly 130 million sq. ft. In the third quarter, net absorption totaled approximately negative 13 million sq. ft. Given the mounting job losses, analysts were expecting net absorption of 25 million sq. ft.

The job losses piling up during this downturn are unlike those of the early 2000s when dot-com companies went bust. This time many big, established companies lost jobs, including major financial institutions.

“If they’re laying off workers, it might be that in their office they might have every fifth desk sitting empty. That’s not necessarily given back to the market [so far] in terms of space,” says Spivey. One reason the space has not yet been consolidated is that many leases have not yet come up for renewal. Some tenants want to hang on to prime space in anticipation of growth.

However, if thousands of tenants give up unused space, that could drive up vacancy rates while depressing net operating income. And that additional space could lengthen market recovery time. “The excess space would have to be burned off before we start to see any real, positive absorption,” says Spivey.

Vacancies roil Phoenix market

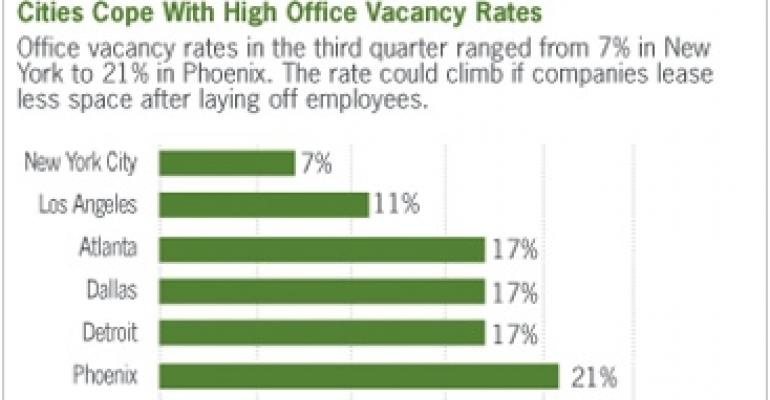

Among the nation’s 20 largest markets, vacancy rates vary widely. The worst-performing office market in the third quarter was Phoenix, which recorded a vacancy rate of 21%.

Overbuilding has presented a problem for Phoenix, which is struggling with a large amount of office space coming on line at a time when the market is already suffering from negative net absorption. Those two trends have magnified the effects of the metro area’s vacancy rate.

Much like Phoenix, the Dallas and Atlanta markets, which recorded 17% vacancy rates, have also experienced a lot of suburban office construction. Because a great deal of land was available and building costs were cheaper than in many other markets, developers became aggressive, adding to the vacancy rate. In Atlanta, developers also undertook a lot of high-rise urban construction in the Buckhead submarket.

In the Detroit area, vacancy rates have risen along with the well-chronicled troubles of the auto industry. Some Michigan developers and property owners face severe competition from financially distressed properties.

“When you’re at a 20% to 25% vacancy rate, you have a supply and demand problem. That’s way too much supply, which is creating a tenant market and driving lease rates down to what they were 20 years ago,” says Scott Marcus, principal of RSM Development & Management, an owner, developer and manager of medical office properties based in Bloomfield Hills, Mich.

The surging vacancy rates have jeopardized owners’ ability to stay in business, he says. When competitors lose their properties to foreclosure, and the properties re-enter the market at far lower sale prices and lease rates, the results can be devastating.

“If those buildings go back to the lender, similar buildings [to his] are being sold for 30% of what we paid for ours.” In Southfield, Mich., for instance, a 200,000 sq. ft. building sold for $5 million. “We’re seeing class-A properties being sold for under $100 per sq. ft., one third of replacement cost.”

Buyers of distressed properties can afford to lease the buildings for a fraction of the going rate, making it even more difficult for market-rate owners such as RSM to compete.