We are a celebratory nation. We throw parties for everything from the major milestones in our lives—our weddings and births—to the Super Bowl games. There is even a website that tells you what National Day it is. (As I write this, it happens to be National Banana Bread Day. Seriously.)

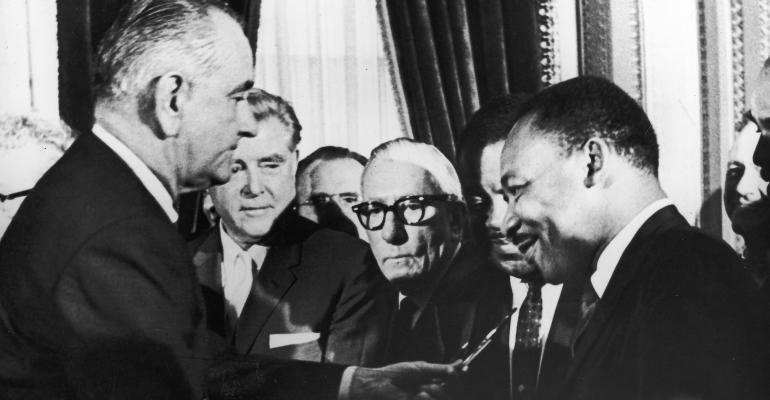

There is a much more serious and more important milestone occurring this year, one that would even overshadow (dare I say it?) the Super Bowl, and yet is so easily overlooked. This year marks the 50th anniversary of the Civil Rights Act, which contained the Fair Housing Act, and was passed into law on April 11, 1968.

Indeed, IREM will be celebrating, in a way, with special treatment of the Act coming up in the March/April edition of the Journal of Property Management. Also on deck are a revamped, online fair housing educational course, premiering this month, and webinars throughout April on the topic.

Fair housing is a concept everyone can get behind. Who, after all, would say they are against it? And yet the practice of fair housing is fully complex and highly nuanced, a sensitive reality that certified property managers whose focus is apartments have to embrace on a daily basis. They stand on the front lines of the issue, ensuring that fair housing lives not only in concept, but in reality—with all of its nuances and complexities

Let’s start with the basics. Fair housing, by act of Congress, is enforced by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. The act over the years has gone through several iterations. For instance, two previously unprotected classes were added in 1988, barring discrimination based on disability or familial status.

As stated in Principles of Real Estate Management, originally published by IREM in 1947 and currently in its 17th edition: “Today, fair housing laws at all levels—federal, state and local—effectively prohibit housing discrimination on the basis of race, color, nationality, sex, religion, age, family status or mental or physical handicap. It is unlawful to refuse or to fail to show an apartment, to not supply rental information (e.g.: rates) or not rent an apartment because of an applicant’s protected status. It is also unlawful to impose different terms or conditions, such as extending different privileges in regard to the rent of an apartment or in providing services based on a resident’s protected class.”

This certainly covers a lot of ground. But here also is where the nuances of best practices come in—and professional CPMs must proactively avoid the myriad sand traps laid out by the subtleties of the legislation. Guidance here begins with a statement of ethics. The Institute’s list of best practices includes the need to “have and enforce a written company code of ethics that defines ethical relationships between the employees of the company and its clients, residents, tenants, vendors, the public and other employees.”

The guiding principle implied therein protects us—which means it protects our residents—against such traps as unwitting breaches of the law. One prime example is what Principles refers to as “steering”: wherein a manager, while not overtly saying, “No,” will dissuade “a prospect who inquires about available property from living at a particular site, encouraging them to look elsewhere, or hiding known vacant space from them.”

The subtleties abound. The legislation surrounding fair housing is well-intentioned, but there are sticking points in how fairness is perceived. For instance, as Doug Chasick, CPM, president of the Peachtree Corners, Ga.-based Fair Housing Institute Inc., told JPM for the March/April issue, “There’s the knotty problem of disparate impact, which essentially is a theory used in fair housing and labor law that seeks to eliminate practices that adversely affect one group of people of a protected characteristic more than another, despite landlord rules that appear neutral.

“One of the biggest myths is that we have to treat everyone the same,” says Chasick. “It’s one of the easiest ways to get into trouble. You have to treat every circumstance the same. When you do try to treat everyone the same you can get into disparate impact.”

It’s a classic case of doing wrong while trying to do right. Simply put, people are not the same. Rules may be applied that are formally neutral, but end up in the realm of disparate impact by adversely affecting one group of people of a protected characteristic more than another.

It is impossible, of course, in the space of this column to illustrate all of the nuances and complexities that define the reality of fair housing. But, guided by the law—as well as by the rules of ethics, the training that is part and parcel of a CPM’s capabilities and yes, even one’s own common sense—fair housing is indeed something to celebrate.

Don Wilkerson is 2018/2019 president of the Institute of Real Estate Management. In addition, he is president and CEO of Gaston and Wilkerson Management in Reno, Nev.