As an increasing number of commercial property owners face upcoming debt maturities, more of them have started to use threats of strategic default as a bargaining tool in negotiations with lenders.

Knowing how reluctant lenders are to take back assets, borrowers of every kind, from big publicly traded REITs to private players with only a handful of centers, have tried this gambit, industry insiders say. Whether or not the strategy works depends in large part on the type of lender and the condition of the property.

“Many years ago, a good borrower would avoid using strategic default because then you would have a stigma on your image that may impact your future borrowing power,” says David T. McLain, principal with Palisades Financial LLC, a commercial real estate lending and advisory firm based in Fort Lee, N.J. “What you are seeing now, when the downturn has led to widespread defaults, they are no longer fearful because their belief is that when the economy recovers, this will be overlooked and they will be able to borrow.”

The dramatic drop in the value of retail properties, coupled with the “everybody’s doing it” mentality, has led many borrowers to consider using strategic default as a bargaining tool, says Gerard Mason, executive managing director in the New York City office of Savills LLC, a real estate services provider.

A recent Wall Street Journal story cited primarily large publicly-traded REITs as the culprits, including Simon Property Group, Macerich Co. and Vornado Realty Trust. But private owners, institutional investors and real estate funds are doing the same thing, Mason notes. Most buyers who invested in commercial real estate in the last three to five years are looking at upcoming mortgage maturities and thinking up ways to restructure, he adds.

In some cases, borrowers might not be trying to paint lenders into corners, says McLain. In instances where a loan is part of a CMBS pool, for example, it’s virtually impossible to discuss restructuring until a default has actually occurred. Only after a borrower stops making loan payments can such loans be worked out. In these cases, lenders often discreetly tell borrowers, “You need to default or we can’t do anything.”

At the same time, the “restructure or we will default” threat tends to hold the least sway with special servicers on CMBS loans because servicers have limited power to alter loan terms anyway, according to Mason.

“They are impervious to that kind of threat and their ability to restructure is practically nil,” he says. “Many times, they take it right back.”

Firms that have not restructured loans in the face of strategic default threats in recent months include PNC Real Estate/Midland Loan Services and Bank of America Merrill Lynch, according to Mason. Both PNC and Bank of America made the Mortgage Bankers Associations’ (MBA) mid-year 2010 top commercial master and special servicer list. Wells Fargo topped the list, with $462.8 billion in special servicing. PNC Real Estate/Midland Loan Services came second, with $307.9 billion, and Bank of America Merrill Lynch came fourth, with $133.4 billion.

However, commercial banks, most notably JP Morgan Chase and Citibank, have been responsive, Mason says. That’s both because they hold the loans on their books and have the authority to change the terms and because they have large commercial real estate portfolios. MBA estimates that commercial/savings bank hold more than $1.6 trillion of U.S. real estate debt outstanding on their books, accounting for approximately 50 percent of total volume. CMBS loans, at $680 billion, make up 20 percent of real estate debt outstanding.

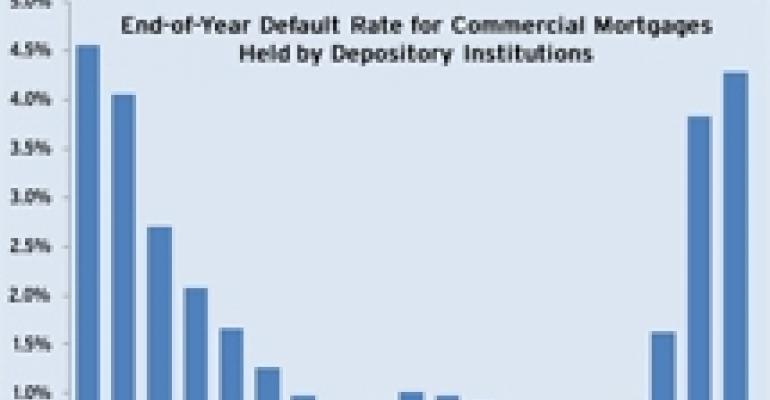

According to analysis of FDIC and bank data by New York City-based Real Capital Analytics, the default rate for commercial mortgages held by depository institutions was at 4.3 percent at the end of the second quarter of 2010—the highest point since 1992.

Life insurance companies also try to work with their borrowers, Mason notes, but are less likely to face strategic default threats because they lent on more conservative terms, with lower loan to value ratios, even at the peak of the real estate boom. In the first quarter of 2010, the delinquency rate on commercial/multifamily loans originated by life insurance companies was below 0.5 percent, according to Savills. The delinquency rate for CMBS loans was above 7 percent and for bank/thrift loans was above 4 percent.

When dealing with traditional lenders, property owners should concentrate on demonstrating that while the property continues to perform well, it’s fallen in value and if the lender will take it back, it will be faced with the same problem, says Mason, whose firm advises borrowers in negotiations. In addition to the losses associated with missed loan payments, assuming control of the asset would result in the lender paying property management fees, which is why lenders normally don’t want to assume ownership, adds McLain. It tends to be prohibitively expensive.

If after several months of negotiations, the lender still hasn’t shown flexibility, it might make sense for the borrower to bring up strategic default. Mason notes that in about 40 to 50 percent of cases, the threat works and results in the lender agreeing to modified loan terms. The new terms might involve a reduced loan amount; a switch to a cash-flow mortgage; and normally, an extended term. The lenders’ receptiveness to the default issue depends on the size of the loan (the bigger the amount, the more reluctant they are to take the property back), the standing of the borrower and the condition of the property.

For example, two weeks ago lenders on the $2 billion, 2.3-million-square-foot Meadowlands Xanadu project in East Rutherford, N.J. voluntarily took over control of the property from developer Colony Capital LLC. McLain says the decision appears to be the result of the lenders’ recognition that the project was unfeasible in its current form. It was conceived at the beginning of the real estate boom in the early 2000s and Colony Capital seemed attached to the original idea. But the market has changed and the lenders, which include Credit Suisse Group AG and Capmark Financial Group, are reportedly seeking a new developer to re-work the project to fit the current environment.

In cases where the lenders can’t imagine the borrower being able to salvage the value of the property down the road, they would rather take it back today than restructure, even if they have to take a loss, McLain notes.

Both McLain and Mason caution borrowers that the threat of strategic default should only be used as the last resort.

“The traditional banks and life insurance companies have very long memories and they don’t forget a borrower who intentionally defaults,” McLain says. “They could blackball that borrower in the future.”